A Century of Ugly Architecture

Le Corbusier’s incoherent 1923 manifesto was indispensable to the ascendency of an ideology that blights cities worldwide, still propagating 100 years later

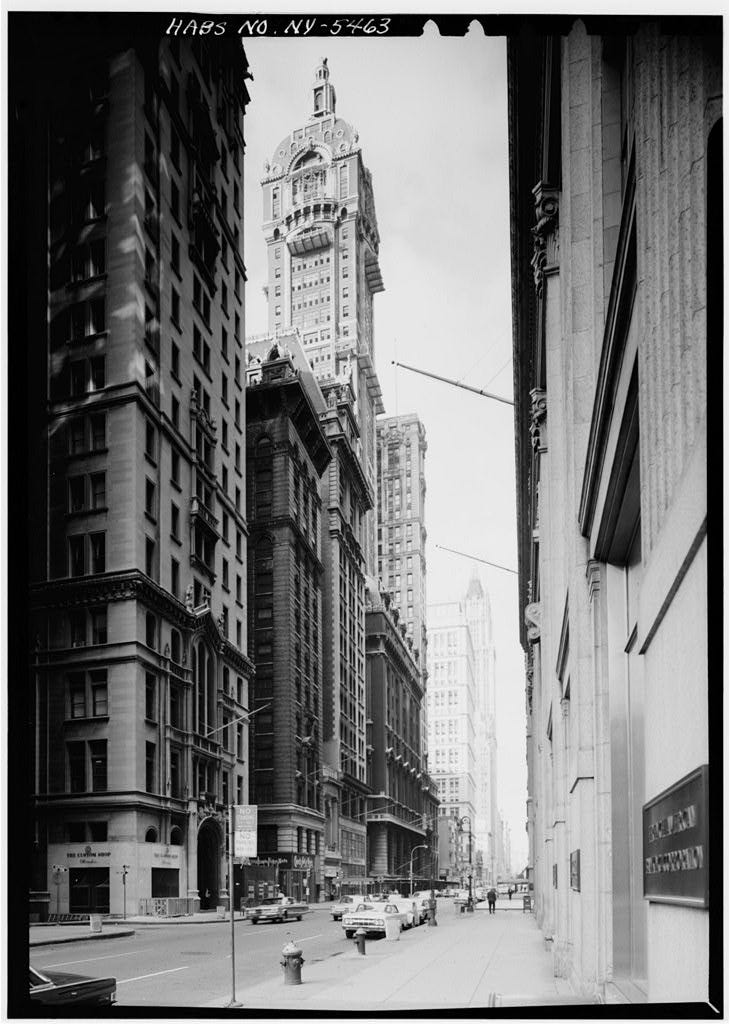

On the way to and from working at an office tower in lower Manhattan, it is not uncommon to find a tourist or passerby standing to marvel at the design, which is the work of an architect called Francis Kimball, built in 1907. The place is not famous or iconic and does not draw crowds, so there are never too many gawkers to cause a nuisance. Plenty of buildings from the period in the area are more beautiful, but every so often a few people happen upon it by accident, gape for a few moments and maybe take photos. This happens day to day, unless the weather is unpleasant.

Adorning the tower are winged gargoyles, parapets, stained-glass windows, and corbels with various stone faces carved into them. The first time I saw all of those exquisite details and endless more, my reaction was similar to others; I stood quietly with eyes wide in wonder for a few seconds. It looks like the sort of place where Batman could be lurking on a ledge at night to glare at miscreants below, while lightning strikes. Then, something else caught me by surprise.

Framed on an interior hallway inside this neo-Gothic masterpiece is a poster. Across the top, in large print, is the name of an extremely influential architect and evangelizer — one who is known for despising and scheming to demolish buildings exactly like the one where the poster hangs. However, that isn’t the worst failing of the man who is honored on the poster.

There are plenty of compelling arguments about influential people in history whose otherwise admirable or redeeming qualities contrast with some awful relationship to either fascism or communism. Those who were drawn to both fascism and communism — a still vast and even more instructive set — could theoretically possess some laudable qualities, or so it can be argued. But vanishingly few among this set have literally made formal proposals to complete projects glorifying both the Nazi and Soviet regimes and been rejected by both because of their poor taste.

At least one man fits the description, however. He is just the sort of person to cause any opponent of “cancel culture” to start rehearsing their arguments all over again, if only to feel sanity return. Surely, if he does not deserve cancellation, then nobody does.

Indeed, even the Hitler and Stalin regimes had enough sense to rebuff the advances of the cartoon supervillain imitator whose name is now somehow admired enough to be framed on a wall poster. That wicked name — Le Corbusier — is a pseudonym, French for “keeper of crows,” a vocation suitable perhaps to some associate of the Joker. Most supervillains adopt pseudonyms, after all, and it was not only in his capacity as an architect (with no formal training, as an aside) that the man originally known as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret publicly evangelized for monstrosity.

Although he never donned a crow costume or lived in a secret lair, he did find spare time (and this is actually true) to be an amateur advisor to a eugenics organization, to pen at least one article opposing the presence of jews in European cities, to attend fascist rallies, and to publish his writings approving of the German and Italian varieties of fascism. After failed proposals to the Vichy regime in Nazi-occupied France and a rejected design for the “Palace of Soviets” in Moscow, Stalin’s own disapproval of the architect was reconsidered by successor Soviet dictators, who fanatically endorsed all the design principles now synonymous with his name and now visible everywhere the Soviets imposed their will. In fact, the Soviet state newspaper, Pravda, called him “the greatest master” of modern architecture. Lucky for me I’m not very superstitious, otherwise the mere utterance of the man’s name (no less than a poster celebrating it!) would seem to me exactly like a curse meant to cast a pox on my house.

Le Corbusier’s single diabolical mission in life was to destroy the most beautiful things in the world and replace them with the most hideous things, though he didn’t see it that way. In his first published book on architecture in 1923, Vers une Architecture (Towards an Architecture), which is one hundred years old as of this year, he explains that, “decoration is of a sensorial and elementary order, as is color, and is suited to simple races, peasants and savages.” Thus, in the “new age,” each person would reside in “a machine for living” devoid of “sensorial” things like color and decoration. It is very much worth reading the entire collection of essays cover-to-cover to fully comprehend the abysmal depths of the man’s raving lunacy, especially now that all the democracies that fought a cold war against Soviet dictators are now packed with the handiwork of the man’s legions of devoted followers and descendent schism sects.

The only humanizing feature of the style is a proclivity for parks and roof-top gardens. He is, despite himself, a human being after all — all too human — and his high-minded intentions are just believable, even amidst the total chaos and confusion of the book. Unfortunately, his parks and gardens offer only views of his own revolting horrors because he makes no accommodation for anything else within the sweeping, panoramic scope of his city-destroying urban planning, leaving nowhere to escape. His park designs themselves are also unattractive. Indeed, the countless parks today built in his style are especially notable for the absence of people visiting them, as compared to parks borrowing from, say, the english garden style, like Central Park in New York City.

According to the “Plan Voisin,” not even the most sinister supervillain plot he masterminded, Le Corbusier would have bulldozed half of Paris to replace its dazzling elegance with eighteen identical towering self-parodies of ghoulishness in which to stack his “machines for living,” although he inexplicably failed to record any maniacal cackle to menacingly announce the scheme. A smaller, parroted version conceived by his acolytes was instead built in a suburb called “The Silent City” and, during occupation, the Nazis recognized it (this is not a joke) as a great design for a concentration camp — a thought not unknown to many observers of the general style — repurposing the project under the name of camp Drancy.

If he could have, Le Corbusier would have disfigured or wiped off the map many other cities. (And the International Style is now famous everywhere for completely disregarding all regional traditions or vernaculars in design, parasitizing the distinctiveness of old neighborhoods, and transforming the individuality of all cities into the same monotonous glass and concrete, like the Borg or some other hostile alien species assimilating every world where it spreads). For example, he planned to level all of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, to build a Blade Runner–like dystopia — for Mussolini — and do the same in Algiers for the Nazi-Vichy-regime-era of French colonists there, not to mention his plans for historic Moscow, Stockholm, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires and others.

Separating the art from the artist is not so simple with Le Corbusier. The “art” is extremely political and the politics are troubling:

The house will no longer be an archaic entity… the object of the devotion on which the cult of the family… has so long been concentrated.

…

Eradicate from your mind any hard and fast conceptions… look at the question from an objective and critical angle, and you will inevitably arrive at the “House-Tool,” the mass-production house, available for everyone, incomparably healthier than the old kind (and morally so too) and beautiful in the same sense that the working tools… are beautiful.

…

But it is essential to create the right state of mind for living in mass-production houses. [Emphasis original]

All that he dismissed in his incoherent manifesto, everything that people naturally find charming, or expressive of a sense of home, is redefined as ugly, lowly, “mere decoration” to be cleared away. Thereby, he fruitlessly tries to reshape human nature’s immutable need for a place to feel at home into a rigid mold fit for some new mutilated creature, judged superior by him, that will live in his “machines” and appreciate his genius, walking around ushering the “new age” all over the place, like toys in a demented model of Shangri-la.

Those unconverted to his mission merely have “eyes that do not see,” as he phrases it messianically. If one could look past the simple fact that Le Corbusier never knew a tyrannical dictator whom he did not admire and with whom he did not seek employment, that would not negate his utopian (which is to say totalitarian) goal inherent in the “art” itself and inseparable from its deepest nature. His style is the perfect physical embodiment of agony and malaise buried beneath quiet alienation.

It is impossible to imagine George Orwell’s 1984 without Le Corbusier’s style of “architecutre” as the set of every torture chamber. What torturer would prefer a Beaux-Arts or art deco room over the International Style for doing the job? Beautiful decorations do not serve to torment, unless the torturer wants to deface beauty as part of the torture — perhaps, to demand that Winston Smith agree to Le Corbusier’s manifesto by having him smash the place to bits? At least Paris was largely spared Le Corbusier’s bulldozer, to my bottomless gratitude, but across the street from where I first discovered his poster is a murder scene in New York City:

Where there was once a soaring colossal burst of beauty beaming out from the glorious Beaux-Arts facades of the Singer Tower, designed by Ernest Flag, completed in 1908, and the Romanesque Revival arches of the adjacent City Investing Building, whose architect adds a unique drama to this story, revealed soon, now there is only one drab deadening black monolith called One Liberty Plaza, designed by Gordon Bunshaft, finished in 1973. Any layperson who is dying to understand, “how did this happen?” can learn the story by reading an interview with Gordon Bunshaft, who explained:

Le Corbusier, in my opinion, was the person who created worldwide modern architecture as a standard through his books… Le Corbusier is the main teacher… Everything that every young architect did was influenced by Le Corbusier, period. Mies didn’t publish as early as Le Corbusier and also Mies didn’t blossom really until he came to this country. Mies was the Mondrian of architecture, and Le Corbusier was the Picasso.

According to Bunshaft, Le Corbusier’s books in the 1920s-30s sparked an “exciting” “revelation” in an entire generation of young architects and this more than anything else is why Bunshaft regards Le Corbusier as the single head of the movement, though other figures like Adolf Loos, Walter Gropius, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe were significant. Unlike them, Le Corbusier was an early and extremely effective evangelizer. The young were particularly moved by Le Corbusier’s books and their careers had begun during a huge wave of new commerce in the post-WWII economic boom, after the great depression had put most traditional architects (and most everyone else) out of business. The newly indoctrinated generation was in its prime working-age years right when business bounced back, as the older generation’s influence had significantly contracted.

If air conditioning’s commercial availability in the 1930s had been delayed a couple decades then Le Corbusier’s style would have been still-born. “All the glass” caused interior conditions like a “furnace” that “would never have worked” without AC. Imagine the black monolith pictured above absent AC. Again, the timing was just right.

Another key ingredient, which surprised Bunshaft, was how many heads of big companies, like David Rockefeller of Chase Manhattan Banking, embraced the new radical style. “They wanted their company to be progressive,” in Bunshaft’s words. Le Corbusier had given form to the concept of progress in the young popular imagination and many titans of industry were among the converted. Although the heads of Bunshaft’s own architect firm SOM, now identified with the style, “weren’t committed” to modernism, the style sold because of this vogue and nobody on the heels of the depression was going to turn away paying customers. It was simply a fad among the youth happening at just the right time in economic history to open a Pandora's box, with air conditioning’s advent as deus ex machina.

Incidentally, the place where Le Corbusier’s poster hangs is called the US realty building, the architect of which was briefly mentioned in the opening: Francis Kimball. It turns out that Kimball — and this is the greatest of all shames — is also the exact same architect of the City Investing Building that was completed in 1908 and demolished in 1968 along with the Singer Tower to make way for Le Corbusier’s “new age.” So, the head of the cult that partly destroyed Kimball’s great legacy is honored in the halls of what still remains next door.

Such a ghastly disgrace to Kimball! (Never mind that Le Corbusier loathed every single aspect of Kimball’s style and would have died to see all the “decoration” blaspheming his manifestos where his poster hangs.) It is as if somebody has built a new monument to Marcel Duchamp’s urinal and Piero Manzoni’s can of shit, and located it not near the vacant parking lot of an “art gallery” in Los Angeles, but in a future dystopia where half of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has been blown to smithereens with half the Rembrandts, Sargents and Turners on its walls — while a plaque hangs inside the remaining half heralding the greatness of the destroyers!

The last laugh has to go to Kimball though, despite the vandals who obliterated his outstanding accomplishment at 165 Broadway, because never once have I seen anyone stoping to marvel at Bunshaft’s monument to Le Corbusier’s “new age.” Most people simply ignore it — the worst insult any artist could possibly suffer. At least the uniformity of its ugliness minimizes its power to distract from Kimball’s still surviving glimpse of grace next door at 115 Broadway.

The great depression did not only put traditional architects out of business. Born in 1909, the same year as Bunshaft, was another young aspiring “new age” architect named Charles Luckman who, unlike Bunshaft, could not find work in his chosen field and took a job as a draftsman in the ad-business instead. After that, he had an unusually successful career that whirled upwards at miraculous speed through many positions including that of president at a multi-million dollar international company called Lever Brothers, in 1946.

As president, Luckman hired Bunshaft to build the now famous 1952 Lever House. It is the second building in the world after Le Corbusier’s co-design of the United Nations building (where dictators are presumed to represent nations equally well to elected leaders) that adopted the “glass curtain” style. The style is now ubiquitous among similarly mind-numbing works of International Style modernism — although at least Lever House also features Le Corbusier’s penchant for parks, however uninhabited in practice, not always mimicked by other followers.

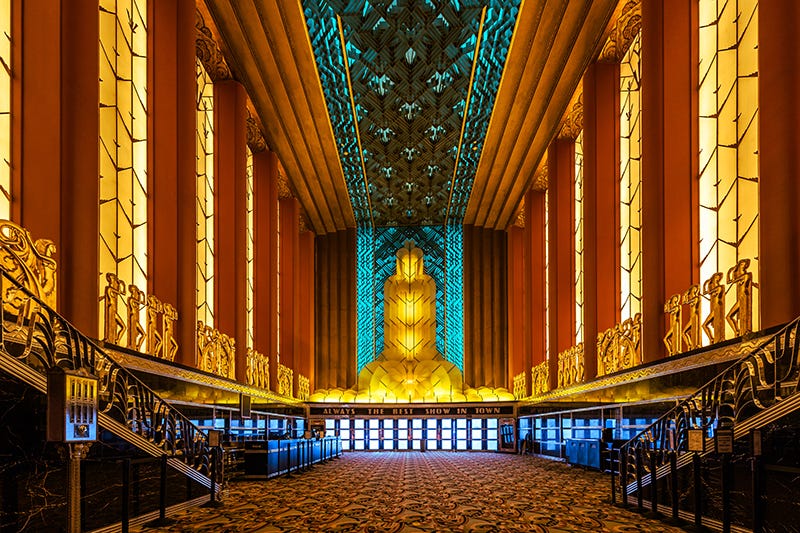

What’s incredible is that Luckman could have enjoyed a spectacular career at the highest level of industry, but he was “inspired” by Bunshaft’s Lever House to quit his job and go back to architecture, where he designed the single ugliest pile of garbage in all of Manhattan: Madison Square Garden — replacing the old Penn Station. The now destroyed train station was of such supreme transcendence that it probably belongs in the same category as the seven wonders of the ancient world.

To redeem the catastrophic loss of such a place, which was not financially sustainable after all, Luckman could have made something else beautiful. He didn’t. (Or maybe the place could have been repurposed into a shopping mall to rival the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan.) But I repeat that Luckman was “inspired” to leave a likely c-suite level career to do this unspeakable deed. Such is the intoxication of the high of modernist ideology to its followers.

If beauty mattered to architects more than originality or the “new age” or their own vanity, as it does to decent people — after all, blue skies and children laughing are not original or new or flattering and confirm the existence of beauty understood universally — then Le Corbusier would not have achieved cult status to a generation of people like Luckman. Perhaps, a replica of one of the seven wonders, say Halicarnassus, similar in size to Madison Square Garden, could have been repurposed from a mausoleum to an arena of stupendous classical grandeur. Alternatively, a coliseum in the style of art deco (a style which spontaneously emerged with no manifesto or leader or new concept of human nature or even any name) could have borrowed from, say, the 1931 Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, at a much larger and grander scale.

To replace old Penn Station with an even more supreme splendor would have at least been a fair trade. Instead, Luckman has given to those of us who are unimpressed with “new ages,” or to anyone with any trace of sense, something that is impossible to look upon without feeling slightly sick. It didn’t even occur to Luckman to be ashamed of this, by all accounts, as he continued designing similar horrors thereafter.

To varying degrees among different people, the fad for modernism became cult-like. Luckman was probably somewhere on this spectrum, but Bunshaft himself was noticeably less intoxicated on the kool-aid than some. He confessed that the first time he visited a design by Le Corbusier, he thought it was “peculiar.” There was no awe like what spontaneously arises regularly at the foot of Kimball’s 115 Broadway. With an MA in architecture from MIT, having worked in the industry when he joined the Army Corps of Engineers at an office job in Paris during WWII, Bunshaft befriended Le Corbusier there and treated him as a man rather than as a god, unlike some. But Bunshaft’s mind was certainly captured by the same vision, if not the articulated ideology, that Bunshaft credits to Le Corbusier alone:

We may have been in love with Le Corbusier, but we didn’t really know what it was. All we knew was that it was simple and white and rectilinear and it had stilts. We were not really serious, because we hadn’t built a building. We didn’t know enough about it… [But after seeing it] we weren’t impressed at all. I thought it was peculiar.

Bunshaft did not consider himself an intellectual and was mercifully not given to speaking as if reading from a manifesto, again unlike so many modernists, but he was simply entranced by the pictures, in particular — drawings interspersed with photos of steel zeppelin hangars, cars, steam ships — inside Le Corbusier’s books, including the one now marking its centenary, which Bunshaft confesses he did not even bother to read much beyond the image captions.

The book is barely readable, only half-lucid at best and crowded with non-sequiturs. Filling the pages of Vers une Architecture are promises that, “the steamship is the first stage in the realization of a world organized according to the new spirit,” which could just as easily appear as a scrawl written on an asylum wall with a broken fingernail. There are absurd interjections — “a chair is in no way a work of art; a chair has no soul; it is a machine for sitting in” — which you wouldn’t want to hear from the man seated next to you on a train. But Le Corbusier’s pictures, the pictures more than anything else, were the lightning rod for an irresistible progressive utopianism among the youth.

It didn’t faze Bunshaft during his first visit that Le Corbusier’s Salvation Army building in Paris was “the shabbiest goddamn thing you ever saw.” Perhaps, it’s too easy to judge Bunshaft now that Le Corbusier’s pictures are one hundred years old and don’t have the air of a “new age.” One cannot help but look at them knowing how many designs borrowing Le Corbusier’s style have proven to be “the shabbiest goddamn thing you ever saw.” (Bunshaft’s own word choice cannot be improved here, to his credit). Yet the style continues to be built everywhere and Le Corbusier’s name is honored on posters. (The fact that the style is so prevalent now in every major city across the globe is not the reason why it is called the International Style, by the way — the term dates to 1932, long before almost anyone had seen it.)

Though I thought I had no sympathy for the enthusiasm to “cancel” historical figures — I am a mere mortal and it actually disappointed me deeply that Le Corbusier had survived all the various mobs tearing through the culture long enough for me to see his poster. The experience of happening upon it inside Kimball’s US Realty building has vividly reminded me of how difficult it is to take a principled position of opposition against “cancel culture.” A detailed analysis against cancellation has by now been done many times by others, convincingly, but let’s consider at least one more reason that is sometimes forgotten.

Similar to statues honoring Vladimir Lenin and Robert E. Lee, posters honoring Le Corbusier are an excellent reminder of how bottomless is the depth of human nature’s potential for idiocy, arrogance, barbarism, tyranny, historical illiteracy and bad taste. This is a permanent feature of human nature and it is good to be regularly reminded of it. Without the reminder, people are more likely to grow incautious and imprudent. At least Le Corbusier’s poster offers this one gift. However, there are ways to refrain from honoring Lenin, Lee and Le Corbusier, without also erasing them entirely or expunging their cautionary mementos of evil for future generations.

In theory, Americans do live in a society where a crowd-sourced fund, which have previously reached into the range of billions of dollars, could purchase One Liberty Plaza and Madison Square Garden, raze them both, and rebuild the Singer Tower, the City Investing Building and the old Penn Station, or even Halicarnassus, again1. Many people assume that the International Style is cheaper than more decorative or traditional styles but this myth has been debunked. If enough people supported it (which is uncertain though modernism is consistently the least popular style in opinion polls), then the logistics, aside from bureaucratic matters, are easy and could be done in under five years. Empire State took thirteen months to build in 1931, but it would take at least a few years longer to build the same thing again today, mostly due to increased red tape — the nearby One Vanderbilt was built in 4 years once the previously standing structures were razed in 2015.

In other words, if Le Corbusier the man and figure of popular admiration is not to be “canceled” through rigidly enforced social taboos and mob rule, then his style can still be incrementally removed from public spaces of honor, at least where land owners and residents support the effort, according to the rule of law, within the rubric of federalism, subject to courts and other institutions intended to ameliorate mob rule. Certainly the worst excesses of modernism can be overturned, without overturning liberal principles or even making any changes to the political order.

An important wrinkle to this idea crossed my mind talking to a woman who grew up in one of the housing projects built in Soviet Russia (not designed by Le Corbusier himself, but in a derivative style). She has naturally grown attached to the memories of her childhood in the project and of course it would be awful to have her childhood home destroyed. Almost nobody she knew had, say, classical oriel windows because almost everyone was housed in similar modernist designs where their own family memories could not be disentangled. To some people, the oriel is associated only with the misdeeds of the state party, who were the only ones with the privilege to enjoy them. Personal associations like these will affect the perception of beauty of any architecture. Razing buildings, no matter how ugly, will have costs difficult to quantify. (Paradoxically, to me, some of the principal victims of the 20th century’s tyrannies embraced the International Style, including former Bauhaus student refugees, when they were building a brand new city out of nothing in the middle of the desert — Tel Aviv — which shows that even those who understand tyranny intimately may not necessarily agree to oppose the mission that Le Corbusier evangelized.)

But if it were popular enough, canceling Le Corbusier’s style in public places of honor according to the rules already in place would actually be relatively easy for citizens in democratic societies to do compared to the subjects of tyrannies. We do not need to resort to the centrally-planned methods of Georges-Eugène Haussmann (who, unlike Le Corbusier, did in fact successfully destroy most of Paris under Napoleon III in order to erect the lion’s share of that magnificent city we see today) or Victor Orban in Hungary (who is also taking an anti-liberal approach to advance beauty there now) or Xi Jinping (who has recently declared that postmodernist architecture is too “weird”). There is no limit to how beautiful architecture can be, and unlike many pipe dreams, building beautiful architecture has been accomplished to great effect countless times in history successfully, although many (but not all!) of these efforts were the work of tyrants.

The liberal democratic world, seemingly growing wobbly in recent years, could still create wonders that dwarf the seven of the ancient world beyond the limits to our imagination, and it wouldn’t take any revolution. Everything needed to do the job is already at hand, save for some persuasion, logistics, and hard work. The proposition is simple enough for any child to immediately agree: beauty — let’s have more of it. Beauty for its own sake is its own reward and everyone understands this.

At the very least, Americans could look with joy toward a more Tocquevillian public effort, done without needing to reach for the malign hand of any demagogues in DC, and not feel shame for the country. Perhaps, some day the fifty states could compete with each other for which one can create something more beautiful than all seven wonders of the ancient world. The contest could be measured by the widest margin of spontaneous audible gasps of awe measured or who can attract the most annual visitors to gape at them for the longest total time over the greatest number of centuries. Incidentally, New Jersey is suddenly a serious contender in this competition, as of 20232. And if democracy in America were ever extinguished, then let there be children born centuries afterward who see an abundance of physical wonders creditable to our highest ideals, as the children of so many generations through the ages have credited wonders like the Roman Colosseum to ancient tyrannies, not always drawing the best lessons from that association to their great beauty.

If even one out of fifty can survive longer than, say, six of the seven ancient wonders, then that would be an accomplishment on par with landing on the moon. Almost certainly nothing can outlive the oldest one, the Great Pyramid of Giza, with its formidable head-start, but why not try? At least then it could be said of humankind that our longest lived wonder was not the work of some prehistoric tyrant whose knowledge of science and technology has been dwarfed by our current age, even as ours still stoops to the preposterous designs of Le Corbusier's small mind.

There is an existing non-profit dedicated to resurrecting the old Penn Station. MSG is owned by MSG Entertainment headed by James Dolan but the city and state governments, transit authorities, and various regulatory bodies concerned, especially the New York City Council Committee on Land Use play large roles in determining the fate of the venue, which is periodically subject to a land use permit renewal process. The most recent one happened in September 2023 and is valid for 5 years. There have been many redevelopment proposals for the site over the years. Underneath the venue is the busiest transit hub in the Western Hemisphere. The federal government is a majority stockholder of the owner of Penn Station, Amtrak, and the board of directors is appointed by the US president.

It is worth spending an hour or so looking at images online of the brand new BAPS Swaminarayan Akshardham temple, pictured above, which I have not personally visited. (I hope to do so soon.) New York’s abundance of excellent architecture is generally considered to overshadow New Jersey but this single temple looks to me from photos like it might be more impressive than any single structure in New York. Bravo New Jersey!! For example, the first twenty buildings to pop into my mind in no particular order when I think of NYC at its greatest are not obviously more impressive when considered individually in a side-by-side comparison with the temple:

Ansonia at 2101 Broadway

Alwyn Court at 180 W 58th St

777 Madison Ave

Woolworth Building at 233 Broadway

American Radiator Building at 40 West 40th St

The Dakota at 1 W 72nd St

Flatiron at 175 5th Ave

The Dorilton at 171 W 71st St

Grand Central Terminal at 89 E 42nd St

Met Life Clock Tower at 1 Madison Ave

New York Life Building at 51 Madison Ave

Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building at 1 Centre St

The San Remo at 145 Central Park West

Chrysler Building at 405 Lexington Ave

Rockefeller Center at 45 Rockefeller Plaza

Metropolitan Museum of Art at 1000 5th Ave

Benjamin Duke House at 1009 5th Ave

Cooper Hewitt at 2 E 91st St

James Hotel at 22 E 29th St

The Beresford at 211 Central Park West

People talk of going back in time to smother baby Hitler in his crib -- they should make a trip to Le Corbusier's childhood bedside as well.

A thorough going condemnation. Bravo.

As a child I was moved from a garden of Eden, the jungle rainforests of Jamaica W.I., to a concrete jungle in Jamaica, Queens. I lived for a time in the then largest co-op in the world modelled on the Ville Radieuse by Corbusier’s most prolific protégé, Herman Jessor.

These places are a concentration camp, a hellscape. People are never alone and always afraid. You palpably feel that whomever designed these places abhor all biological life, us included.

Folks ask me why I hate Modernism so much.

Well, it hated me first.